If you are in or near New York City Sunday will be your last chance to see "the most elaborate flower show and cultural exhibition ever presented by The New York Botanical Garden" so don't miss it.

As the days become shorter, the northeaster forest floors are blanketed with asters that are complimented by a far more famous member of the aster family. In Japan, a nation where saying it with flowers is a highly disciplined art form, these autumn days are celebrated with and this time of year was once called the "chrysanthemum months."

The chrysanthemum has influenced western art for many years but for centuries the Japanese had treated their Imperial horticultural art of Kiku like a state secret. Until November 15th, for the third and final time, the New York Botanical Garden offers far more than an ordinary flower show, a fascinating cultural exchange and different view of the art of flowers.

A Chinese philosopher once said, "If you would be happy for a lifetime, grow chrysanthemums."

This relationship between people and flowers began a long time ago. The short day flower (so named because most of these daisies come up in autumn when the days are shorter) were first cultivated in China as a flowering herb as far back as the 15th century BC. Horticulturists there cultivated yellow-flowered chrysanthemums as long ago as 500 B.C.

The chrysanthemum is one of the The "Four Gentlemen" in Chinese art. The four plants that are used to depict the unfolding of the seasons are the plum blossom for spring, the orchid for summer, the chrysanthemum for autumn, and the bamboo for winter. "Chu" is honored by the Chinese city Chu-Hsien which means Chrysanthemum City. In the Chinese autumn chrysanthemums play a significant role in the Double Ninth Festival.

Since being exported over to Japan in 8th century A.D. the flower has found an even more important role in Japanese culture.

So taken were the Japanese with this flower that they adopted a single flowered chrysanthemum as the crest and official seal of the Emperor. The chrysanthemum in the crest is a 16-floret variety called "Ichimonjiginu." Family seals for prominent Japanese families also contain some type of chrysanthemum called a Kikumon – "Kiku" means chrysanthemum and "Mon" means crest. In Japan, the Imperial Order of the Chrysanthemum is the highest Order of Chivalry.

Japan has a National Chrysanthemum Day, which is called the Festival of Happiness.

“There are Japanese who practice a certain kind of aestheticism all the time, and they get into growing perfect flowers—such as the chrysanthemum. And just on the exactly right evening, when a single prized chrysanthemum is due to come into its perfection, and just on the exact evening when not only the perfect bloom occurs, but the full moon, and the night, and the weather all come perfect together—the triumphant gardener will invite friends over, to admire that single perfect bloom, and to speak ecstatically all night about this perfect flower, and the perfection of the night—and the perfection of the perfect, when it comes all together at once.

And all who wonder there drink simple green tea together, to keep the perfect flowered night persistent—until just before perfection passes out away. And they move very gently all through the night—Thrilled! Just to be there, in the fragile brief coincidence of natural perfection.” – Adi Da, from The Happenine Book

The chrysanthemum is the official flower of Japan and has become a symbol of longevity, power, dignity and nobility. In the Japanese garden the cycle of life from birth to death is reflected in the quiet passage of a year in the Garden. The chrysanthemum that is also a metaphor for homosexuality in Japanese poems is celebrated, quite democratically each autumn in Kiku Matsuri throughout the parks, gardens and homes of Japan.

Akihito is the is the 125th Japanese monarch to occupy the Chrysanthemum Throne. While the cycle of life has been honored for generations in the Japanese garden the four Imperial styles of kiku that are presented in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory Courtyards were once shared only with a select few and the art of Kiku was a closely guarded secret.

After a five-year cultural and educational exchange, gardeners at The New York Botanical Garden learned this art from Kiku master Yasuhira Iwashita and other Japanese Chrysanthemum Masters. Some of these Japanese traditions are very labor intensive and the autumn displays are the result of much patience and skill.

The growing method? In November or December take a small shoot. Pot it up. Grow it on. Fertilize, water, pot on, pinch, support, continue training week after week, month after month. Meticulous attention to detail has masters of chrysanthemum cultivation spending a year training plants that will bloom for a couple of weeks before starting the whole process over again.

After learning how to grow and train these extraordinary plants Kiku: The Art of the Japanese Chrysanthemum at the NYBG was the first time that the techniques and styles developed and displayed at Shinjuku Gyoen were presented outside of Japan.

Wooden pavilions are carefully erected for each of these four different disciplines that will go on display at botanical gardens and public parks throughout Japan every autumn. These fancy wooden sheds are called uwaya. They are built of bamboo and cedar to provide both staging and shelter for the flowers. In Japan part of the art is a brand new display every autumn but here in the New York display the same uwaya is used each year;

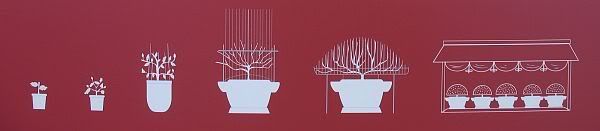

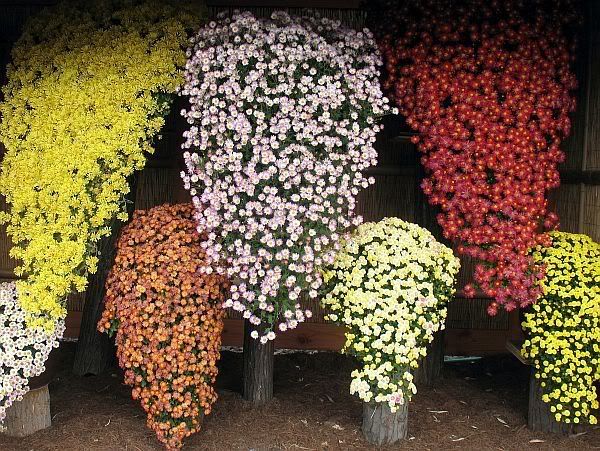

Ozukuri or "thousand bloom" is the most fascinating. A single chrysanthemum plant is trained to produce hundreds of simultaneous flowers in a massive, dome-shaped array. An illustration beside the Ozukuri uwaya helped to explain this painstaking effort that produces a miniature hill of flowers from just one plant!

Once these plants are ready for display they are shown in specially built wooden containers called sekidai. At that point the supporting collars have become complicated frameworks that lead up to and support each individual flower.

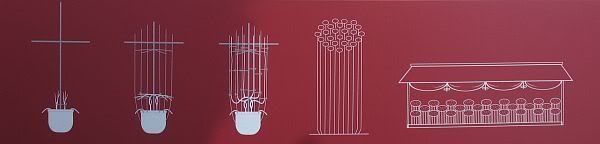

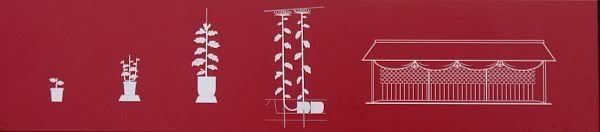

Shino-tsukuri or "driving rain" uses not one but two plants. The training method of these flowers are almost as intense. As the two plants grow their tips are pinched off to encourage side growth until there are twenty-seven branches. Each is then tied to a vertical stake to grow straight and tall and the height is carefully adjusted until the desired slanted circular design is achieved.

The Shino-tsukuri displays utilize an old-style chrysanthemum called Edo, the former name for Tokyo. The Edo flower has three different kinds of petals and as the flowers mature some petals curl inward while others remaining open. This gives the blossoms a pinwheel effect by display time.

Kengai or "cascade" which actually translates to "overhanging cliff," is not from one or two plants trained but hundreds of smaller flowered chrysanthemums. These flowers are trained on a boat-shaped framework that is then angled to resemble flowers growing down the face of a cliff.

Kengai has been familiar to western gardeners for many years and is also called the "bonsai chrysanthemum" because the method is a common practice used to evoke age with the miniature trees.

Ogiku or "single stem" display are plants trained to reach up to six feet tall with one enormous perfect flower balanced on top.

Each uwaya features exactly 108 single-stemmed plants placed in diagonal rows. The diagonal rows of flowers in pink, yellow, and white are meant to echo the colors and patterns of the tazuna, the bridle reins of the Japanese emperor.

Since New York and Tokyo have similar climates Kiku is an outdoor display that is complimented with another Japanese art. Under the glass of the conservatory Bonsai are displayed and that is an even easier way to understand the Japanese relationship with plants. Obviously the stunting of trees in crowded city dwellings is a means of enjoying and respecting the forest from an urban setting.

Volunteers who devote time to keeping these connections with nature are on hand to explain this art that has also been practiced in America for many years. I find it both interesting and comforting that every one of these volunteers I've talked with grows (or stunts) these tiny trees in in tiny Manhattan apartments.

Another Japanese connection with the American northeast that is displayed as it has been in all the previous chrysanthemum shows are the typical autumn colors enjoyed by both cultures that can be found at Kiku. Did you know that in autumn the Japanese hillsides become dappled canvas of scarlet, gold and orange just like her in Eastern North America? The source is the same in each region. There are more that twenty species of maple (kade in Japanese) compared with the nine found in all of north America.

There are also outdoor bonsai on display. A miniature forest of Japanese Maple (Acer palmatum) in autumn glory;

A Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinesis) against a backdrop of Japanese Maple.

Another Japanese Maple against a back drop of bamboo and Victorian Architecture;

The Karesansui Garden probably represents the definition of Zen for many in the west. These dry landscapes composed of rock and raked sand are both spiritual and an abstract representation of the larger natural world. The displays last year were designed by Marc Peter Keane and meant to capture the Japanese mountainsides in both autumn and winter. These outdoor displays now represent an example of West meets East. Masses of chrysanthemums and river pebbles replaced the raked sand of the traditional Karesansui;

For a very interesting contrast and convergence of cultures there was a bamboo sculpture last year. On a rainy day the sculpture in the foreground and the Victorian Palm Court in the background was a warm exchange;

For many years the simpler serenity of the Japanese garden in autumn was displayed at the NYBG and those areas can still be enjoyed.

This is the final year that the New York Botanical Gardens will present Kiku as a Celebration of Autumn where many cultural differences and convergences can be observed. From a western perspective, at least for me, it is hard to understand the disciplines developed in the more than one thousand years the Japanese have been training chrysanthemums.

Coming from a culture that has only know the chrysanthemum since the 17th century, one of the cultural differences is vast and easily misunderstood. It is hard to understand any art without understanding the culture of the artist and I made the mistake of associating Kiku with mentality of formal European gardens. The art is not a means of mastering the natural world but a discipline meant to bring people closer to the understanding of the plants. On a previous visit it was explained to me as a Zen thing. Multitasking and Zen have never worked together and the art of Kiku is about focusing on doing one thing and doing it perfectly.

It will be a shame to see Kiku end and the traditional chrysanthemum views on the grounds won't be the same without that educational exchange.

For even more information about Kiku Matsuri there is this link from the Takarazuka Family display in Japan and and last years press release from the New York Botanical Garden.

No comments:

Post a Comment